Blink…And You’ll Miss It!

Verisimilitude, apart from being a long word that feels fancy to say (especially if you’re a Film Student *wink *wink), it’s a term that describe sa films appearance and its overwhelming sense of truth or reality. This isn’t wholly about reality and everything we see in a given moment whilst watching a feature, but the realism that is perceived in a particular world seen in a film. It’s a construct that binds the plausibility of stories and characters presented in a myriad of genre’s and is often or not exploited by the film-maker to purposefully suspend audience’s disbelief or misconceptions to what they’re seeing and become wholly immersed. Inherently, there are many formalities that film-makers like to employ to create this nuanced feeling. However, if there’s one distinctive and profound methodology that is adhered by the most, it’s the implementation of the continuous tracking shot; a long tracking shot that disregards subtle transitions and creates this effect that you’re watching the drama/action unfold in real-time. The most notable and palpable example of a continuous tracking shot that I’ve seen is within Alfonso Cuarón’s Children Of Men where we see Clive Owen’s character guiding the recently pregnant heroine of Kee through a war-zone looking for her baby. The simple use of this technique allows us not only to become immersed, but to naturally make us feel tense. This is what Sam Mendes does so effortlessly within his latest of 1917 with the guidance of master cinematographer Roger Deakins by using the long-tracking shot throughout the entirety of the narrative; documenting every encounter that unfolds in the story. With it adopting such an appealing aesthetic however, how does Mendes’ film compare to preceding features of similar ilk that employ the continuous tracking shot to enhance their story?…

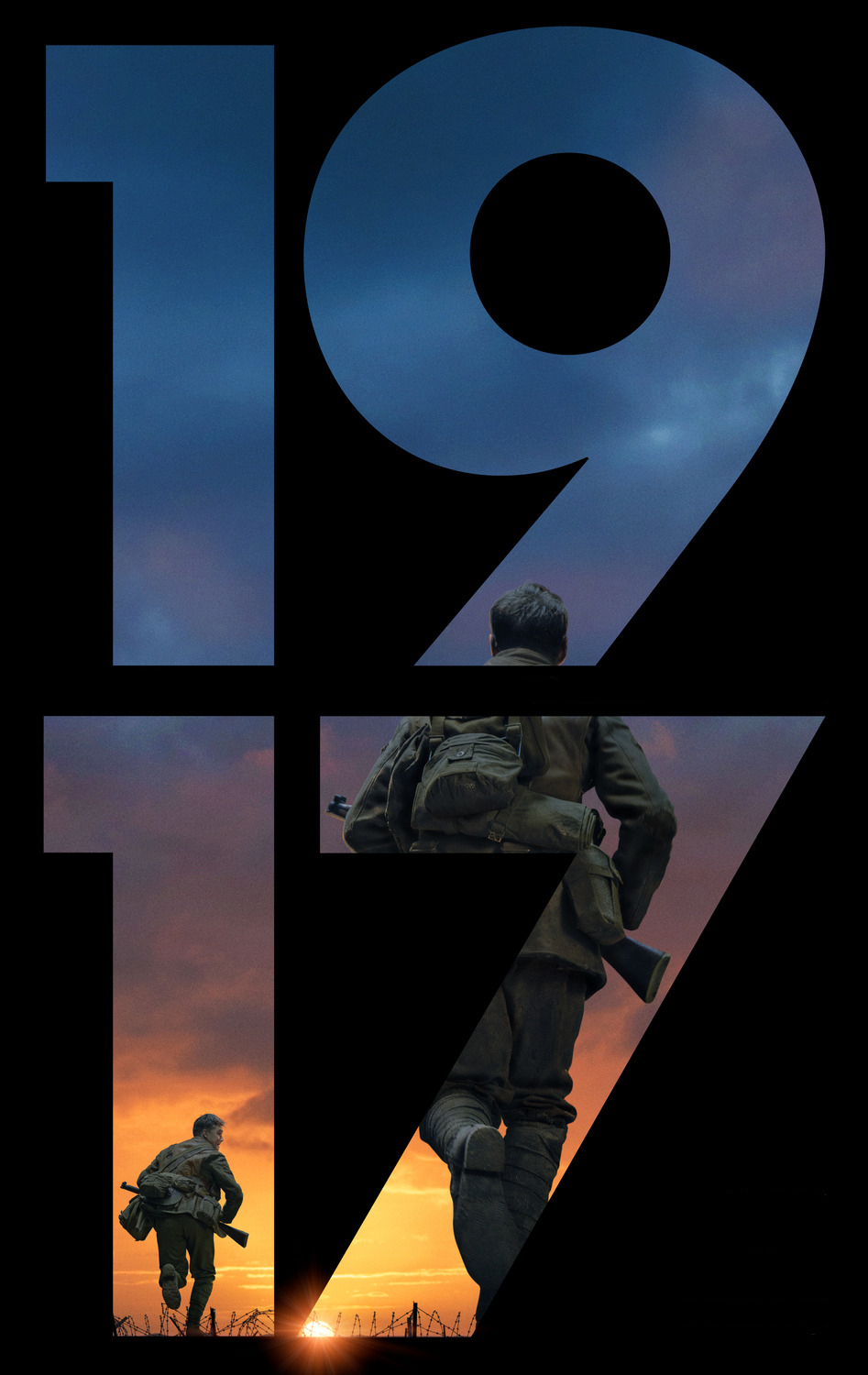

During World War I, two British soldiers, Lance Cpl. Schofield and Lance Cpl. Blake, receive seemingly impossible orders. In a race against time, they must cross over into enemy territory to deliver a message that could potentially save 1,600 of their fellow comrades; including Blake’s own brother. In crossing through No Man’s Land, rigged mines and abandoned/derelict towns, can both Schofield and Blake deliver the message in time? Or, will there efforts come to unsavoury fruition?…

As much as it may seem that Sam Mendes has approached his first world war drama in manner which isn’t of the norm of the said film-maker, who commonly focuses on the perspectives of his characters seen most notably in his Oscar winning film of American Beauty, you only have to take a look at his recent approach to see how much of an adapting auteur Mendes has become. Here, he amalgamates his own personal methodology to a visually stimulating yet ambitious means that subsequently engulfs your attention to the point of excitement yet unease all at once. One can only look at the opening of the previous James Bond film of Spectre, of which Mendes directed, to see the said film-makers nous for using the continuous shot method. Taking place in a memorable sequence set amid Mexico City’s day of the dead festival, the camera tracks a masked figure through crowded streets, into a hotel lobby, up an elevator, out of a window, and over the rooftops to a deadly assignation. As audacious as it seemed for a Bond film, and rather too fancy, it serves as the film’s strongest asset in being an attention-grabbing curtain raiser that dives straight-into the action. For his latest venture into damning and harrowing locales of abandoned trenches, derelict countrysides and chaotic landscapes of war, Mendes’ interest of the ‘one-shot’ format has certainly peaked; this time stretching it to a films entirety. Like Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman or Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity, 1917 uses several takes and set-ups, seamlessly conjoined to give the appearance of a continuous cinematic POV, albeit with periodic ellipses. The result is a populist, immersive drama that leads the viewer through the trenches and battlefields of northern France, as two young British soldiers attempt to make their way through enemy lines on 6 April 1917. There are evocations, too, of Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, not only in the unflinching depiction of battlefield violence, but also in a plot device that sets soldiers searching for a brother in a desperate quest for redemption. However, unlike Spectre’s explosive opening that’s accompanied by the continuous frame of the camera, what’s perceivable to deduce from 1917’s introduction is the spontaneity of the situation that both characters of Schofield and Blake are placed in and the inherent predicament that they’re faced with. As much as you have an inkling of what escapades we’ll be shown, it’s the quaintness of the beginning that I found most profound; how the opening fade into the perspective of the one of the central characters and their subsequent walk/talk with the other protagonist provides this feeling of inherent spontaneity. They are characters that have been caught in this messy situation through chance and, through watching the film, your mindset is naturally attuned to the characters as well. While the said film’s cinematography can’t go unnoticed, of which we’ll discuss soon, what’s equally imperative and rather underrated to fathom is 1917’s narrative. Despite what a few naysayers say of Mendes’ feature, of how it upholds a simplistic story-line that doesn’t do anything out of the ordinary, The script, which Mendes co-wrote alongside Krysty Wilson-Cairns, quietly and beautifully brings into question how we frame the word “heroism” in terms of individual action versus collective bravery. In one of many scenes where Blake and Schofield are rushing across French countryside in a race for time, It’s revealed Schofield traded the medal he won for fighting at the Somme for a bottle of wine. Blake is enraged by the idea. “It’s just a bloody bit of tin,” his friend snaps back. It doesn’t make him special. You can instantly sense his guilt – is it not fate alone that separates him from the fallen? As much as both Blake and Schofiled are arguably drawn into elaborate set-pieces that could easily cross-over towards an Indiana Jones film, they’re set-pieces non-the-less that are executed through the impactful formalities of Thomas Newman’s underappreciated score.

What significantly drives 1917’s narrative however is, of course, the innovative camera-work provided by Roger Deakins. With meticulous attention to detail (plaudits to production designer Dennis Gassner) and astonishingly fluid cinematography by Roger Deakins that shifts from ground level to God’s-eye view, Mendes puts his audience right there in the middle of the unfolding chaos. There’s a real sense of epic scale as the action moves breathlessly from one hellish environment to the next, effectively capturing our reluctant heroes’ sense of anxiety and discovery as they stumble into each new uncharted terrain. There is little respite, interspersed with genuine shocks and surprises that wholly immerses us. It maybe one long continuous shot, which is clearly edited in a fashion to seem like one continuous take, but what’s paramount to fathom is the manner in which the camera ducks and dives gracefully, swooping around balletically. Indeed, from the choreography that seamlessly amalgamates with the fluid cinematography, it’s clear to state that this is a film that has been meticulously planned, to the inch, to the millisecond. What is a bit of negligence is this very precise nature; how everything happens in exactly the right place at exactly the right time. At times, you can’t but feel as though you’re physically being led through a roller-coaster ride filled with certain grandeur, but also that expectancy of this very same grandiose manner.

Yet, for all its visceral efficiency and clear attempts in successfully creating a grounded and realistic atmosphere through the artistry of the camera, what can’t go understated are the more low-key moments; sequences when we’re confronted with the simple human cost of war. Echoing Peter Jackson’s monumentally moving documentary They Shall Not Grow Old, 1917 works best when showing us the boyish face of this conflict. This is captured perfectly through the portrayal of the two characters of Blake and Schofield who both equally project ravaged innocence in a situation where there very youth is sucker-punched through a myriad of plights and endeavours. There is less banter as events become graver. This is epitomised through the pulsing score of Thomas Newman who ratchets our ears through the body-strewn carnage of no-mans land, deserted farmhouses and bombed-out churches. The audio is often unforgiving from the moment the film becomes consequential and this is thanks to Newman’s musical cues which are filled with piercing melancholia and lurking threat. In a film where music plays an integral part to the tension of the scenarios we see, what’s most significant of the audio is a singular moment. This is best emphasised in a scene in which we find ourselves in a wood where a young mans sings The Wayfaring Stranger. It’s an interlude that brings the audience and characters together in silence.

Granted, what made Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk so special to perceive was the craftsmanship in poetically condescending musical scores with the corresponding scenarios depicted; heightening each of the stories shown to the point where jeopardy comes quickly, and you care. However, while many people may certainly disagree with this, I think from a formatic point of view, Sam Mendes’ 1917 provides a war story that implements familiar war film tropes, but clearly and successfully goes the extra-mile in showcasing its hell-scape story through visual means that are sumptuous to gaze at. As much as many can respectfully argue the films narrative simplicity, and how it the latter half of the feature may feel as though it’s a string of set-pieces, Mendes’ feature is very much a stylistic exercise designed to integrate its story to its cinematography and snaring musical score, and it works. Dare I say it? With it portraying war with enormous panache, and documenting every movement of the central characters to the point where you feel as though you’re there with them on this Sam and Frodo-esque venture, Mendes’ film is probably one of my favourite war films…

On that note, it’s time for me to end this week’s Film Review. As always everyone, thank you for reading my latest Film Review of 1917 and if anyone wants to share their thoughts on the film or review itself, then you’re more than welcome to comment down below. For next week, I’ll be discussing My Hero Academia: Heroes Rising and how this anime spin-off feature does everything to wow it’s devotees whilst amending problems that the T.V. series suffers itself… With that said, thank you once again for reading my latest Film Review and I hope you’re all having a nice weekend! Adieu! 😃💣😲

★ ★ ★ ★ ★ – Alex Rabbitte