Charmingly Spooky

It’s always difficult for any film-maker to impose their distinctive filmic aesthetics to a popular genre type which revels in films that essentially implement a formula and other cinematic tropes over and over again. While there are many features within the genre types of horror, and especially superhero films, that all stick to a mode of means that necessarily satisfy the demographic watching, it’s a rarity to stumble upon a feature within these genre’s that purposefully inform complex and intricate contexts alongside the norm aesthetics. A fairly recent good example where a film belonging to a popular genre type utilises differentiating filmic tactics to impose a change and something new, would be James Mangold’s Logan; a superhero feature that deliberately swept aside the grandeur of action set-pieces and applied emotional and compelling story-telling. As much as it’s arguable to look upon Alejandro Amenábar’s The Others and recognise how subtly it brings forth techniques that are synonymous with horror-generic films of the past, it’s a film that also permitted cinematic approaches that were uncommon to notice in other similar contexts. In creating a languorous yet eerily dreamy backdrop, Amenábar’s spooky visualisation ardently amalgamates a classical style with the contextual substance; something which many films of the same genre can’t willingly execute…

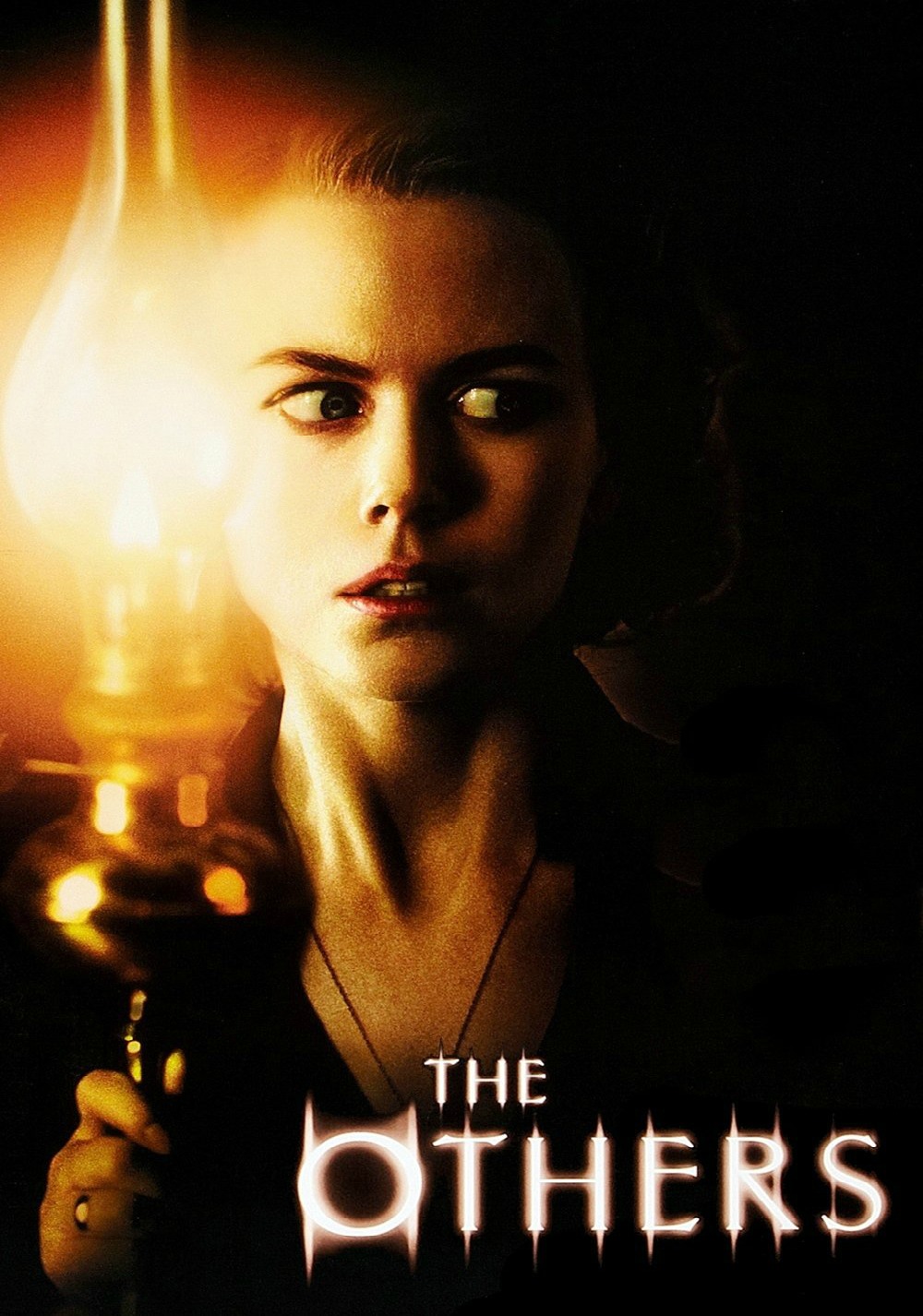

In 1945 Jersey, Channel Islands, Grace Stewart lives in a lonely old house taking care of her photosensitive children of Anne and Nicholas. After her previous servants went missing, Grace willingly accepts the offers of work from three new servants; the ever-whimsical Mrs. Mills, the mute maid Lydia and the gardener Mr.Tuttle. However, since these three servants have entered the home, strange events occur and Grance begins to wonder if it’s her sanity getting the best of her, or if there’s something much more in the house that lurks among them…

One of the fundamental nuances that a horror-specific feature has to inhabit to occupy the observer, is to sustain a level of suspense from the inception of the story, right up-to the 2nd act. Writer, director and composer Alejandro Amenábar in creating The Others, with classical-hitchcockian filmic techniques, assuredly assimilates the right amount of suspense through the dark backdrop of the opaque household that metaphorically transpires this notion that everything we see and notice of the characters and their actions, can’t be trusted. Indeed, from the opening credits of which we see hand-drawn illustrations of disturbing and harrowing figures and set-pieces that seemingly transpires from the book form onto the screen like a classical Hollywood film where we see Nicole Kidman’s character of Grace abruptly scream, Amenábar sets the tone in a spooky fashion that is demanded. Anything less than a mere whimper, of a case where we were introduced to the characters and their harrowing predicament in a subtle and controlled fashion, would have dramatically negated the fluidity of the contextual structure. As briefly noted in the introduction, while it’s evident to notice throughout the entirety of The Others that Amenábar cleverly manipulates the use of various classical styles, as we’ll discuss, in line with an arguably cliched story-line that is simple and easy to predict in what will happen by the time of the conclusion, it’s this amalgamation of style and substance alone that makes Amenábar’s feature so effective and compelling to watch. One of the conclusive reasons why this combination of a purposefully used classical cinematic style and a simple story-structure works is down to the fact that Amenábar has total control over his material. Besides taking the helm and constructing a combination of camera shots to visually trick our perception of what’s going on within the confides of the story, as seen in a sequence when Grace gazes through the mirror to notice one of the door’s she locked is mysteriously open, Amenábar is also the individual who is responsible for not only the script that is filled with religious connotations but also the composed haunting yet emotional musical score. As we’ve explored before in the previous film review of Matilda, where Danny DeVito took liberty into directing and acting in said film, it can be jarring to notice the presence of the creator since it can be a subtle distraction from the story at hand. In the case of Amenábar and his pursuit in delving into the multitude of creative aspects surrounding The Others, it’s not as disturbing since there are many elements in which this director thrives upon and understands the classical sterilisations that he’s implementing. Take the construction of the cinematography for example, Amenábar fully expresses the conflicting theme of religion (expressed in many classical Spanish horrors) with techniques commonly seen within the German Expressionist films. Like many expressionistic films of the later stages of that era in German film history, the expressionism in The Others does indeed lack very exaggeration due to the fact that backdrop and the lighting maintain a profound sense of darkness right through the running time. However, with their being moments in which characters are in shock by the reveal that have been bestowed upon them in a dramatic turnabout and amalgamating the uses of static shots and quick pans to metaphorically emphasise the hesitant nature of one of the characters movements, Amenábar seamlessly borrows themes of the said cinematic movement by expressing moments that include insanity, madness, mirrors and a dark urban setting. As much as it’s fascinating, first time around, witnessing the mystery surrounding the house that Grace and her children are fully miffed at, one of the more intersting aesthetics that Amenábar utilises in alluding to the mysticism of the narrative is the balancing use of light and dark lighting. Most of the film takes place within dark rooms and dim hallways with flames of candles in lanterns as the only source of light. Throughout the entirety, the audience is kept in the dark and it is not until we reach the explanatory twist when sunlight pours into the house and our minds; symbolising this perspective that the characters now know everything of what’s happened to them. While many will ponder and despairingly notice the fact that The Others isn’t a horror film that implements moments that are designed to jump you out of your seat, it does take liberty in expressing sequences that are chillingly disturbing at first glance. One of the sequences that demonstrates this, which was a scene that unsettled my viewing experience in watching this film first time around, is the subtle moment in which Grace stumbles upon memento mori relics of the photographed dead within the haunted house. While this scene may not be as chilling as the moment in which Grace look’s at her child, Anne, in shock noticing an old woman’s face, the photograph’s of the dead in which Grace stumbles upon in the attic of the house is just unnerving to watch simply because this was a spooky practise that took precedent in the Victorian era. With this subtly utilised, it not only further expresses Amenábar’s expressionistic film-making in utilising a mesh of classical styles to appear as contemporary, but emphasises the attempted realism that The Others is trying to convey in tangent with the main context being about ghosts and otherworldly entities. The one blaring problem that stood out in another consecutive viewing of this film was involvement of Christopher Ecclestone’s character as Charles and it interrupted the flow of the mysteriousness that was consistently building up in the backdrop. While Ecclestone’s inclusion as the war-torn soldier who comes home to the Stewart household does add another subtle dimension to Grace’s well-being, it does rather disrupt the mysticism that was engaging to watch.

Aside from Amenábar’s rather successful and seamless efforts of mixing various classical filmic styles to not only exaggerate the contexts of the film through various camera techniques but to also accentuate a realistic sensibility in accordance with the supernatural events, Nicole Kidman’s portrayal as the affirmed yet conflicted Grace, and her interaction with the children, as well draws about this greater sense of verisimilitude. In portraying a role that isn’t formalised to be a typical horror film heroine, Kidman’s enactment of Grace is fuelled with realism rather than generic acting to introduce the audience to a flawed, emotional and conflicted woman. In differentiating from the norm, what is intriguing to gaze at the character of Grace is her unpredictability and how she strafe’s away from being a heroine that we want to root for. Instead, it’s the opposite. As she becomes dysfunctional around her children, denying anything they say in terms of what’s going on around the household, the heroine status that many would assume to place around Kidman’s character is concealed; revealing to us a contrasting ‘heroine’ which still loves and ‘protects’ her children, but steadily becomes obsessed and mad of what’s happening around her, of which she can’t believe. The children, specifically Alakina Mann’s enactment as Anne, are equally as creepy and untrustworthy. As much as one can point out the notion of realism being further explored through the interactions amongst the siblings of the film, of which we see Anne bullying little brother Nicholas, it’s just as thrilling to be encapsulated by Anne’s uncertainty; you never get a true grasp of her true intentions which is placed similarly with Grace’s flawed realistic characteristics. The same can be said of Fionnula Flanagan’s understated performance as Mrs.Mills who’s facial expressions also leave us wanting knowing more than she already knows.

While it’s understandable that film-lovers may share similarities and comparisons from this feature with M.Night Shyamalan’s film of The Sixth Sense in terms of the supernatural contexts, story twists and the way’s in which they keep the audience guessing through the varying degree of camera shots, Alejandro Amenábar’s suspense-filled horror thriller of The Others stands as a unique film that occupied the substance of simplified ghost story through the classical cinematic means that ultimately differentiates from any other feature within the same genre. In seeing many different types of horror films that have come to, unfortunately, adopt the same predictable formula of adding inevitable jumps scares and ludicrous twists that aren’t compelling to be engrossed by, The Others is rather distinctive due to its way in which it manages to complement both the style and the substance; creating something visually stimulating with enough engaging context to warrant multiple viewings. It’s ultimately a breath of fresh-air in comparison to most other films in the same genre and it’s even more impressive when Amenábar controlled and mastered nearly all the aspects of the production. As I’ve said with multiple film reviews in the past, It’s a rarity to notice films in this day-and-age that provide something that is familiar yet surprising and enjoyable. It really is a shame. However, if there’s one horror film to turn to, it’s this Amenábar feature…

On that note, it’s time for me to end this week’s review. As always everyone, thank you for reading my latest retro film review of The Others and I hope you’ve all enjoyed the read!!😉👻, If anyone has an opinion on either my review or on the film itself, feel free to drop a comment down below. I do apologise for not putting-up a film review for so long, there are a multitude of reasons I haven’t provided you with anything; including my lacklustre writing of late, my training for the 10K run that I just did and simply not having the time to sit and write about a film. I know…I messed up a tad bit!! However, I will hopefully bring you a new film review of Studio Ghibli’s co-production of The Red Turtle which look’s intersting to say the least!! 😀🐢. Anywho, I want to thank you to everyone for reading this week’s Blog Post and I shall see you all soon!!…I hope 🤞 Have a nice week!! Adieu!! 😊😎✌

★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ – Alex Rabbitte