Animation Craftmanship

As arguable as it is to dismiss this point of view, stop-motion animation – which, unlike computer and traditional hand-drawn cel animation, utilises real objects shot frame by frame, with tiny adjustments made in-between – is a medium that has defied crude expectations and is a mode of means that has been effectively utilised in contemporary film-making. From the ever-knowing Wallace & Gromit short and full-length animated features produced by Aardman Studios, to the visually sumptuous pieces that studio Laika have seemingly displayed through both Coraline and Kubo and the Two Strings, stop-motion animation has never been more fruitful than it has shown to be today and, similar to how the hand-drawn technique is admired for its inherent contrast to CG animation, should be more appreciated for the craft and dedication that goes into it. While many weren’t initially invested in the depiction of Roald Dahl’s whimsical novel, Wes Anderson’s approach on constructing Fantastic Mr. Fox, amalgamating the visual style that’s projected from implementing stop-motion with Anderson’s own auteurist and eccentric visual and contextual tendencies, was fairly interesting and rather understated considering what was achieved. Much of the same can be said in regards to his latest venture into animation once again, in the form of Isle of Dogs; another full-length stop-motion animated feature that evenly echoes Anderson’s preceding efforts in providing original whimsy and a heart-warming story…

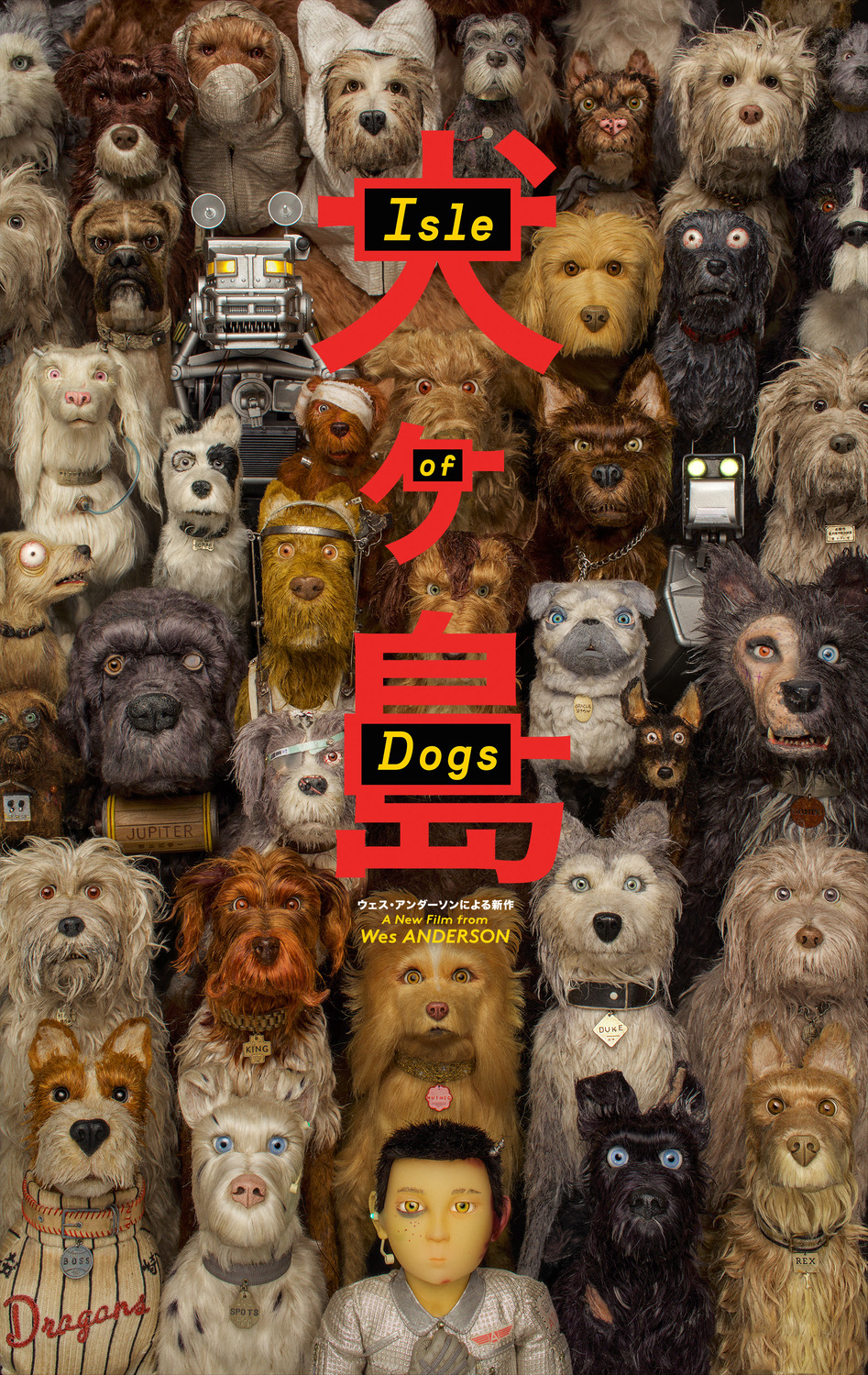

Set in “the Japanese Archipelago, 20 years in the future”, dog-hating Mayor Kobayashi banishes the mutts of Megasaki City to Trash Island, starting with his household’s loyal Spot, due to the responses to the outbreaks of snout fever and canine flu. Bereaved by the loss of his pup-friend, Kobayashi’s 12 year-old, gap-toothed nephew and ward, Atari Kobayashi, runs away, steals a plane and flies to this junk-yard dystopia where he hopes to find his long-lost dog, but instead encounters “a pack of scary, indestructible alpha dogs” With the assistance of a pack of newly-found mongrel friends, Atari begins his journey that will, inevitably, decide the fate and future of Megasaki’s entirety…

Aside the controversy that has arisen from critics and audiences alike noticing the subtle nuances towards racial stereotyping and cultural appropriation, seen arguably within the films plot-point of Japanese-speaking characters not being subtitled in contrast to the anthropomorphic dogs speaking English and not understanding what the character of Atari is saying (when Rex says, “We get the idea. You’re looking for lost dog, Spots.”), what’s paramount to simply perceive of Anderson’s return to animation, in the form of Isle of Dogs, is its inherently peculiar yet entrancing story that all audiences can take something away. While it’s a film that can be conceivably seen as a animated-feature that echoes today’s moral issues of discrimination and immigration, where abrupt figure-heads determine the outcome of who and what should remain in a specific prefecture, it’s also a simple tale of a boy and his dog; upholding similarly poignant overtones of Bon Joo-ho’s Okja. In similar vein to Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill duo of films, Isle of Dogs respects the culture and heritage of Japanese ethnics whilst also providing a distinctively hyper-stylisation that’s synonymous with Anderson’s film-making efforts; as well as the type of cinematic releases that are admired and appreciated in Asian cinema. While it has this charming charisma and ironic buoyancy of Anderson’s previous Fantastic Mr.Fox, the film, at times, never once shies away from completely providing moments of bite. From a dog getting its ear bitten off depicted early in the film, to a character being told to literally “stop licking your wounds” and a surprisingly graphic kidney transplant, Isle of Dogs can be delightfully ghoulish when it needs to but is playfully executed in a manner that won’t leave any young audience member scarred by what they’ve seen. If there’s one negligence that Anderson’s film could have done without, it’s the reliance of unnecessary flashbacks to provide context to a specific situation. Apart from the very beginning of the film, which neatly outlines the films scenario and the historical backdrop of Megasaki City and Major Kobayashi’s dislike for dogs, the disproportionate amount of flashbacks that covet the structure of the film very much halts the progression of a story that should be linear in the running-time that it has. Very much damaging the pacing as well, these particular moments of gratuitous contextualising can cause some sequences to feel uneven. There’s also the odd stylistic choice of not providing English subtitles for the Japanese-language characters and scenes; where, instead, these moments are either narrated in English or literally interpreted by another person or dog. While this specific filming construct didn’t bother my experience when watching the film, it’s rather understandable from another person’s perspective as to why this lack-of English subtitles for the spoken Japanese-language is a bad one. Arguably, it not only presents this lack of empathy or any sought of connection with the Japanese characters, it’s a distinct factor that doesn’t add anything significant or artistic to a film that has so many qualities going for itself. Much of the same can be said for the third act of the feature where the charm that was seamlessly established soon diminishes with the outcome of the story being resolved with brawn, rather than wit.

In being no stranger to stop-motion, Anderson, similarly executed in his preceding animation of Fantastic Mr. Fox, displays Isle Of Dogs in a way that is beautiful yet rough all at the same time. Similar to how the dogs are presented, the stop-motion work has an endearingly scratchy quality to it that feels like raspy drawn comic-book being brought to life. Roughness around the edges of well-constructed and detailed buildings that fits seemingly with the symmetrical perfection of the frame that Anderson visually strives to get across, it’s clearly evident how much hard-work has gone into making the various colourful yet downtrodden locations that comprise the story of Isle Of Dogs. Accompanied by Alexander Despalt’s contrapuntal bass score which heightens the films more tense sequences, it’s the little details of practicality and ingenuity that delight your eyes with hypnotic wonder. From the scuffles of fights that are animated as if they were taken from a Looney Tunes cartoon, with random arms and legs sticking-out from a swirling dust cloud, to cotton wool clouds, cellophane rivers and abstract miniatures that fill the silver-screen, Anderson’s team of animators keep things admirably physical and further exemplifies the majesty and unpredictability of the stop-motion method; like what Anomalisa and Kubo and the Two Strings have done in recent years.

Alongside the ever-noticeable toy-box esque visual style that the aforesaid director distinctively uses in all of his films, Anderson once again presents an assemblage of acclaimed actors to feature in Isle of Dogs who all feel devoted and somewhat self-aware in their respective roles. While the film’s attention slowly focuses its attention on Chief, a gruff and horribly scarred stray solemnly voiced by Bryan Cranston, his doggy companions equally grab the screen by the scruff of their paws with some memorable moments and one-liners. There’s a sleek and gossipy mountain dog named Duke (Jeff Goldblum), a neurotic hound, named Rex (Edward Norton), who can’t pass-up on an opportunity to call a vote, and a well-groomed and acrobatic show-dog, named Nutmeg (Scarlett Johansson). While each of these familiar voices, and more, idiosyncratically consolidate with Anderson’s vision and the inherently ‘unconventional’ narrative, there’s not one of them steals the silver-screen for their own. While Frances McDormand’s role as Interpreter Nelson, a character who essentially subtitles what the Japanese characters are saying, gets heavily under-utilised, there are also voice performances from the likes of Bill Murray, as the jumper-wearing dog Boss, and Greta Gerwig as an American exchange-student, who questions and conspires Mayor Kobayashi’s decision to send the dogs on a remote junk-island, that can be questioned as to why they should be this film in the first place.

Despite these little nitpicks however, Wes Anderson conjures-up a marvellously entrancing stop-animation, in the form of Isle of Dogs, that not only bestows staggering and well-constructed backdrops and character figures in a symmetrical visual style, but displays a charming and absorbing story that can be read in many ways. For all the disease and hardships that’s visually emphasised in the rough-tough landscapes which our fantastically empathetic canines take refuge in, the world of Isle of Dogs, both formally and contextually, is a beautiful one and certainly wouldn’t grind the eyes to see it a few more times…

And with that, it’s time for me to end this week’s Film Review. As always everyone, thank you for reading my latest Film Review in the form of Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs and I hope you’ve all enjoyed the read! 😉 If anyone has an opinion on either the film or on the review itself, you’re more than welcome to share your thoughts down below. For next week, I will be presenting you with another Film Review, discussing and sharing my thoughts on one of Marvel’s most ambitious films – Avengers: Infinity War. Thank you for reading this week’s Blog Post and I hope you’re all having a nice weekend! Adieu! 😀😐🐕👀

★★★★☆ – Alex Rabbitte